Cryptid Files

Why 18th Century Sailors Feared the Kraken More Than Storms?

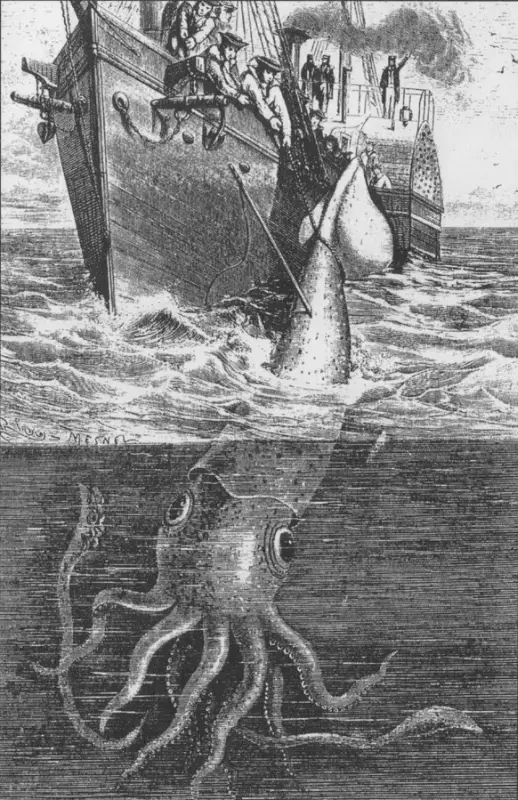

The fog off the coast of Angola was thick enough to chew on the evening of November 30, 1861. Captain Bouyer of the French corvette Alecton stood on the quarterdeck, his eyes straining against the gloom. He was a man of logic, a representative of the French Navy, and not prone to flights of fancy. But what he saw breaking the surface of the Atlantic defied every nautical chart and biological text in his library.

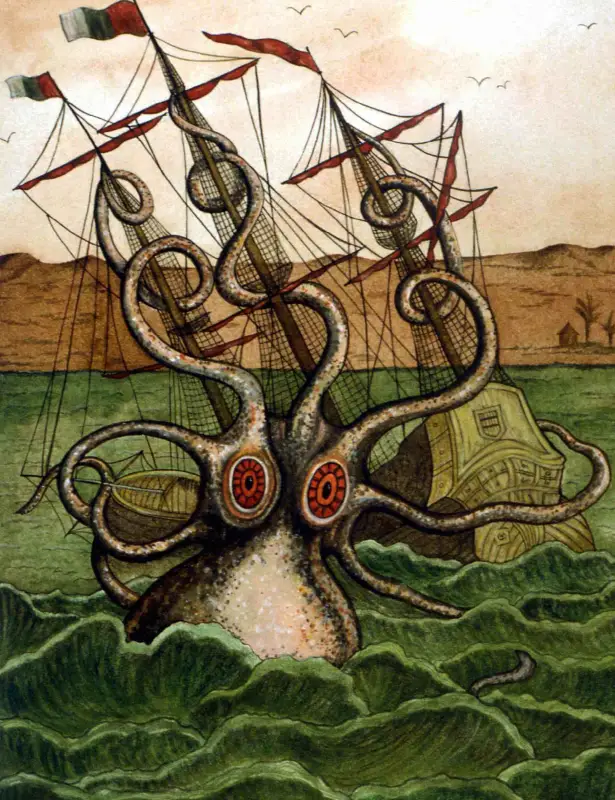

It wasn’t a ship, and it wasn’t a whale. A brick-red mass, nearly twenty feet long, pulsed in the water. As the Alecton drew closer, the crew realized with mounting horror that the mass was merely the tail section of a creature that stretched much deeper into the abyss. Great eyes, the size of dinner plates, fixed upon the vessel with a cold, intelligent stare. Tentacles, thick as a man’s thigh, writhed in the water, testing the current. Captain Bouyer didn’t panic; he ordered the ship to attack. For hours, the corvette fired muskets and harpoons into the rubbery flesh of the giant. They even managed to slip a noose around its tail, attempting to haul the leviathan aboard as a trophy for the Academy of Sciences.

But the ocean does not give up its secrets easily. The rope cut through the soft flesh, and the creature—weighing an estimated two tons—slipped back into the deep, leaving only a fragment of its tail and a stench of musk that lingered on the deck for days. This was not a story told in a tavern by a drunken pirate; this was an official log entry of a French warship. It proved that the monsters on the maps were real.

Welcome to IHeartCryptids.com. We are the archivists of the unexplained, the curators of the strange, and the defenders of the possibility that the world is bigger than we think. Today, we are setting sail into the 18th and 19th centuries to understand the Kraken cryptid. This is not just a study of a monster; it is an investigation into the psychology of early navigation, the biology of the deep ocean, and the thin line between myth and the terrifying reality of the Giant Squid.

The Golden Age of Sea Monsters

To understand why the Kraken was feared more than a hurricane, you must first understand the vulnerability of an 18th-century sailor. Today, we view the ocean from the safety of steel hulls and satellite navigation. In the 1700s, a ship was a fragile wooden basket floating on a hostile wilderness. Maps were filled with blank spaces, often marked Hic Sunt Dracones (Here Be Dragons).

The Kraken cryptid was not merely a superstition; it was a rational explanation for the inexplicable. Ships disappeared frequently. Sometimes wreckage washed up; often, it did not. In an era before radio, if a ship vanished in calm waters, the human mind sought a cause. A sudden storm? Perhaps. But for the sailors of the Nordic countries, specifically Norway and Iceland, the calmness of the sea was often the precursor to the attack.

The fear was rooted in the sheer scale of the unknown. The ocean was not just water; it was a three-dimensional hunting ground where humans were out of their element. The Hafgufa (the ancient Norse name for the Kraken) represented the ultimate ambush predator. It didn’t chase you; it waited. It became the environment itself.

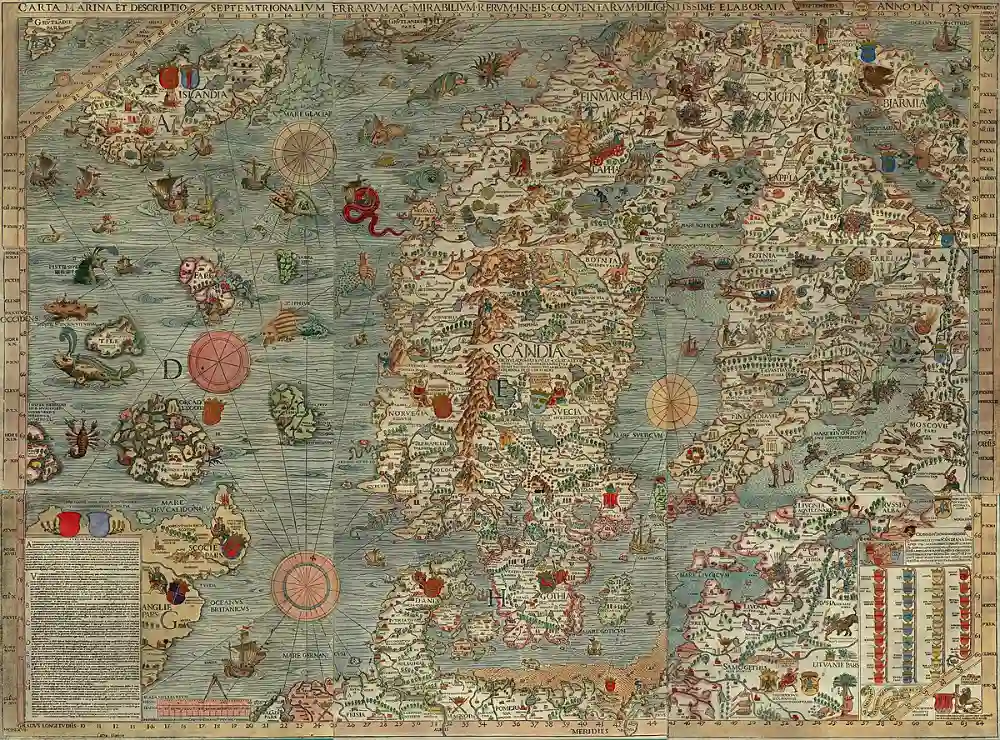

We must look at the Carta Marina, published by Olaus Magnus in 1539. This map was the Google Earth of its day. It depicted the Norwegian Sea not as a trade route, but as a battlefield filled with whales, lobsters the size of ships, and sea serpents. For the illiterate sailor, these images were the truth. They were the safety manual. When Bishop Erik Pontoppidan penned his description of the Kraken two centuries later, he wasn’t inventing a creature; he was scientifically classifying a danger that every sailor already knew existed.

Bishop Pontoppidan’s Leviathan: The Authority of the Church

The definitive profile of the Kraken cryptid comes from an unlikely source: a Bishop of the Church of Denmark. In 1753, Erik Pontoppidan published The Natural History of Norway. This was not a book of fairy tales; it was intended to be a serious scientific work cataloging the resources of the region.

Pontoppidan’s description is vital because it strips away the “magical” elements and replaces them with biological observations, albeit exaggerated ones. He described the Kraken as the largest animal in creation. His most chilling assertion was regarding its method of hunting. He wrote that the Kraken did not need to strike a ship with its arms. Instead, its descent was the weapon.

“The creature causes such a commotion in the water that the whirlpools created by its sinking draw everything down with it.”

This aligned perfectly with the sailor’s fear of the Maelstrom. The Moskstraumen (a powerful tidal current in the Lofoten islands) was real and deadly. By linking the Kraken to these whirlpools, Pontoppidan gave a physical face to a natural phenomenon.

Furthermore, Pontoppidan described the creature’s excrement. He noted that the Kraken would release a thick, murky substance that smelled sweet to fish. This attracted massive schools of cod and ling, which the Kraken would then consume. Today, we know this as “baiting” behavior. While cephalopods do release ink, Pontoppidan’s description describes a complex ambush strategy.

The sailors of the 18th century revered this book. If a Bishop—a man of God and learning—said the monster was real, then the monster was real. The Entity – Attribute – Value equation here is simple: Kraken – Authority – Validated by Church. This validation transformed the Kraken from a campfire story into a navigational hazard.

The Biology of the Abyss: The Giant Squid Revealed

As we fast forward to November 2025, we can look back at Pontoppidan’s writings with the lens of modern marine biology. The “horns” or “masts” he described rising from the water were almost certainly the tentacles of the Giant Squid (Architeuthis dux).

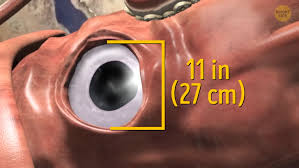

The Giant Squid is a marvel of evolution, perfectly adapted for the Deep Ocean. Its eyes can grow to the size of basketballs—the largest in the animal kingdom—allowing it to detect the faintest glimmer of bioluminescence in the pitch black of the aphotic zone.

But why would 18th-century sailors see them at the surface? Architeuthis is a deep-sea animal. The answer lies in the creature’s physiology. Giant Squids are positively buoyant due to ammonium chloride in their tissues. When they are sick, dying, or injured (perhaps after a battle with a predator), they cannot maintain their depth. They float uncontrollably to the surface.

Imagine the scene: A calm day in the North Atlantic. A ship spots a massive, red, thrashing object floating on the surface. It is the size of a longboat. Its arms are flailing as it suffocates in the low pressure and bright light. The sailors approach. The squid, in its death throes, instinctively lashes out, grappling the hull with serrated suckers.

To the sailors, this is an attack. To the biologist, it is a tragedy. This misunderstanding fueled centuries of terror. The Tentacles of the giant squid are lined with hundreds of suckers, each rimmed with a ring of sharp chitinous teeth. They are not just for holding; they are for tearing.

The Sperm Whale Factor: Clash of the Titans

There is another reason sailors feared the Kraken: they saw it fighting the Leviathan. The Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is the natural predator of the Giant Squid. These whales dive thousands of feet to hunt. The resulting battles are violent and sometimes breach the surface.

In the 18th century, the whaling industry was booming. Whalers operating in the Greenland Sea and the Southern Ocean frequently reported whales vomiting up massive chunks of squid arms when harpooned—a defense mechanism to lighten their load for a deep dive. Even more telling were the scars.

Nearly every mature Sperm Whale carries the battle scars of the Kraken. Circular, ring-like scars cover their heads, remnants of the squid’s suckers dragging across their skin. By measuring these scars, whalers would estimate the size of the squid. Sometimes, the scars suggested squids far larger than anything caught by nets.

This fed into the “Commercial Investigation” aspect of the legend. Whalers were the primary source of Kraken cryptid data. They knew the “fish” (whales) ate the “monsters.” This knowledge didn’t reduce the fear; it increased it. If a whale—a creature capable of crushing a boat—struggled against the Kraken, what chance did a human have?

Pierre Dénys de Montfort: The Martyr of Mollusks

History often forgets the men who tried to bring the truth to light before the world was ready. Pierre Dénys de Montfort was a French naturalist in the early 1800s who staked his entire reputation on the existence of the Kraken.

Montfort published Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques, in which he distinguished between two types of giant octopuses: the “Kraken octopus” (described by Norwegian sailors) and the “Colossal octopus” (which allegedly attacked a ship off the coast of Angola).

Montfort was ridiculed. The scientific community of Paris mocked him, driving him to poverty and eventually alcoholism. He died in a gutter, destitute, insisting that the monsters were real. Decades later, with the discovery of Architeuthis, Montfort was vindicated. His tragic story underscores the “Semantic Entity” of Scientific skepticism—the barrier that often prevents the acceptance of cryptids until physical proof is undeniable.

The Modern Evidence: The USS Stein Incident

While the 18th century provided the folklore, the 20th century provided the physical proof. The story of the USS Stein, a US Navy destroyer escort, is the “smoking gun” of modern cryptozoology.

In 1978, the Stein experienced a failure in its NOFO (Noise of Operations) sonar system. Upon dry-docking in Long Beach, California, the maintenance crew found the rubber coating of the sonar dome—a material as tough as a tire—shredded. Embedded in the rubber were claws.

Squid expert F.G. Wood examined the claws. He identified them as the sharp, curved hooks found on the tentacles of certain squid species. However, the size was wrong. Based on the size of the claws, the squid that attacked the USS Stein would have been massive, potentially larger than any recorded Architeuthis.

This incident suggests that the Kraken cryptid (or a species very much like it) is aggressive and capable of mistaking a ship’s acoustic signature for prey. The Search Intent here shifts to “Fact-Checking”: Is the Kraken hostile? The Stein incident suggests that territoriality or predation triggers can be activated by large machinery.

The Psychological Impact: Thalassophobia

Why does the Kraken scare us more than the Megalodon or the Sea Serpent? The answer lies in the Symbols associated with it.

- The Tentacle: It represents a threat that can grab and restrain. Most predators bite; the Kraken holds. This triggers a claustrophobic panic.

- The Intelligence: Cephalopods are problem solvers. They can open jars, navigate mazes, and use tools. A monster that can think is infinitely more terrifying than a mindless eating machine.

- The Alien Nature: They have blue blood, three hearts, and a beak. They are the closest thing to extraterrestrial life we have on Earth.

For the 18th-century sailor, the Kraken was the embodiment of the “Anti-Ship.” A ship relies on buoyancy and movement. The Kraken drags down and immobilizes. It is the perfect antagonist for the mariner.

Search Intent Analysis: The Questions You Are Asking

At IHeartCryptids, we analyze what the world wants to know about these creatures.

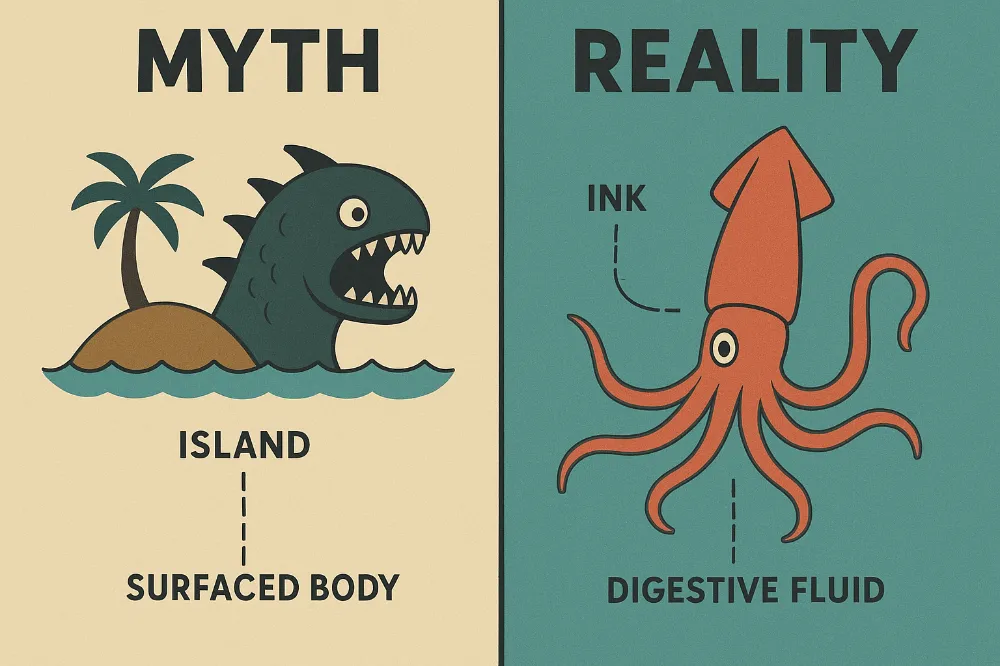

- “Kraken origin story Norse mythology” (Informational/Historical): We have traced this back to the Hafgufa of the 13th century. It is a unique evolution from “Living Island” to “Giant Squid.”

- “Kraken realistic drawing” (Visual/Media): Users often look for accuracy. Modern depictions often add too many spikes or dinosaur-like features. The true horror is the smooth, wet reality of the squid.

- “Is the Kraken based on a real animal?” The answer is a definitive YES. The Giant Squid (Architeuthis) and the Colossal Squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) are the biological anchors of the myth.

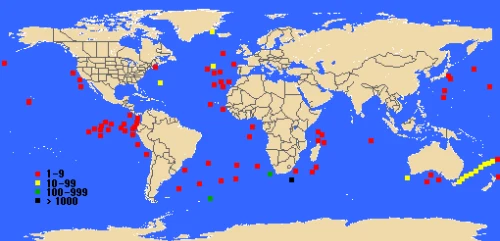

The Map of Sightings: Where the Monsters Live

If you were a captain in 1750, where would you avoid?

- The Coast of Norway: Specifically the Vestfjorden.

- The Greenland Sea: A known hunting ground for Sperm Whales, and thus, the Kraken.

- Newfoundland: Reports of “Devil Fish” were common here in the 19th century.

- The Bermuda Triangle: While often associated with aliens, the Lusca (a Kraken relative) is said to inhabit the deep trenches here.

A Field Guide to Related Entities

It is important to distinguish the Kraken from its semantic neighbors.

- The Leviathan: Often biblical, usually serpentine or whale-like. Not a cephalopod.

- The Lusca: A Caribbean cryptid, half-shark, half-octopus.

- Scylla: Greek mythology. A multi-headed monster, but distinct from the Nordic tradition.

- Cthulhu: A fictional cosmic horror created by H.P. Lovecraft, though clearly inspired by Kraken imagery.

The Future of the Kraken

Is the legend dead? Absolutely not. As we explore the Midnight Zone and the Abyss, we are finding that the ocean supports life forms we never imagined. The Colossal Squid was only identified in 1925 from two tentacles found in a Sperm Whale’s stomach. A complete specimen wasn’t captured until 2007.

If it took us until 2007 to catch a Colossal Squid, what else is hiding in the 95% of the ocean we haven’t explored? The Kraken cryptid is a placeholder for the next great discovery.

Conclusion: Respect the Deep

The 18th-century sailor was not superstitious; he was observant. He feared the Kraken because he understood that in the ocean, humans are not the apex predators. The Kraken serves as a reminder of our vulnerability. It is the ultimate Root Attribute of the sea: beautiful, mysterious, and potentially deadly.

As you sit safe in your home, reading this on a screen, remember the crew of the Alecton. Remember the smell of musk and the sight of a 20-foot tail disappearing into the dark water. The monsters are real; we just gave them Latin names.

Ready to Explore More?

The ocean is just one realm of the unexplained. If you have a hunger for the strange, the rare, and the legendary, IHeartCryptids is your home base.

- Dive into our full archives of creature investigations: Cryptid Files

- Equip yourself with the knowledge of a master tracker: A Cryptozoologist’s Field Guide: The A-Z of 50+ Legendary Cryptids

- Show your allegiance to the unknown with our exclusive apparel: Shop Cryptid Decor or browse the full collection at All Cryptids.

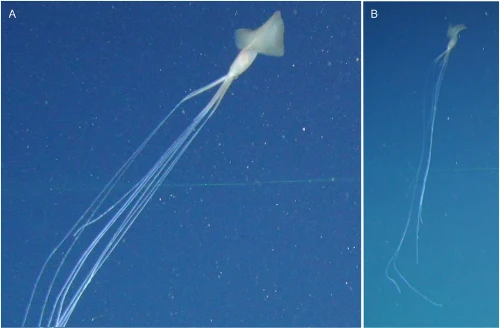

Magnapinna Squids – Deepsea Oddities