Cryptid Files

Squonk Cryptid: Why This Pennsylvania Legend Weeps in the Dark?

The temperature in the Pennsylvania wilds dropped sharply as the sun retreated behind the ridges of the Allegheny Mountains. It was late October 1909. J.P. Wentling, a man whose name would later become synonymous with one of the strangest events in American folklore, was not sitting by a warm fire. He was crouching in the mud, holding a lantern that flickered against the darkness.

Wentling was not hunting for sport. He was following a sound that had plagued the local lumber camps for weeks. It was a sob. The low, rhythmic weeping echoed through the valley, sounding uncomfortably human. He traced a glistening trail of moisture on the forest floor — viscous, salty, and warm to the touch.

As the lantern light caught loose, warty skin trembling in the shadows, the weeping stopped. Wentling lunged, throwing a burlap sack over the miserable shape. He felt the weight of the creature — alive. His heart raced with the thrill of capture.

But the triumph was short-lived. By the time he untied the sack in his cabin, there was no prize waiting — only a puddle of acrid water, and the remains of a creature that had dissolved in its own grief.

This narrative marks the defining tragedy of the Squonk cryptid.

At IHeartCryptids.com, we serve as the archivists for the unexplained. We look past the campfire stories to find the biological and cultural roots of America’s monsters. Today, we open the file on Lacrimacorpus dissolvens, exploring the biology, the history, and the enduring mystery of the creature that weeps in the dark.

The Anatomy of Melancholy: What is a Squonk?

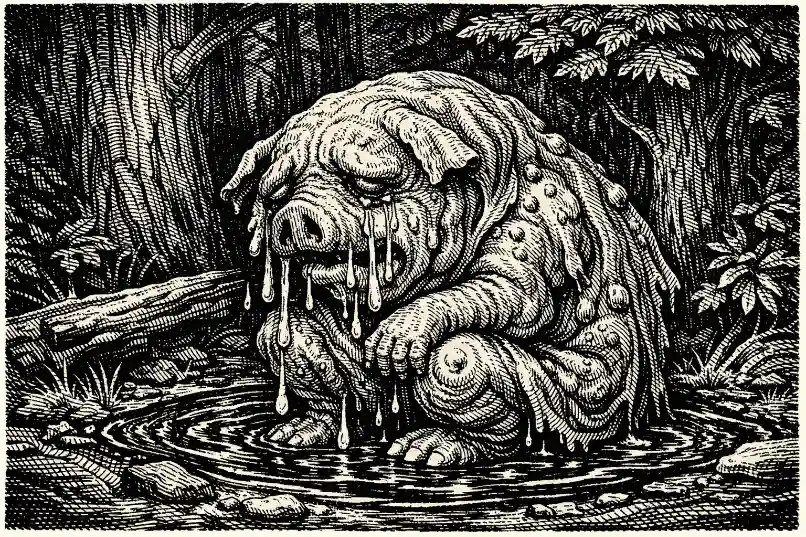

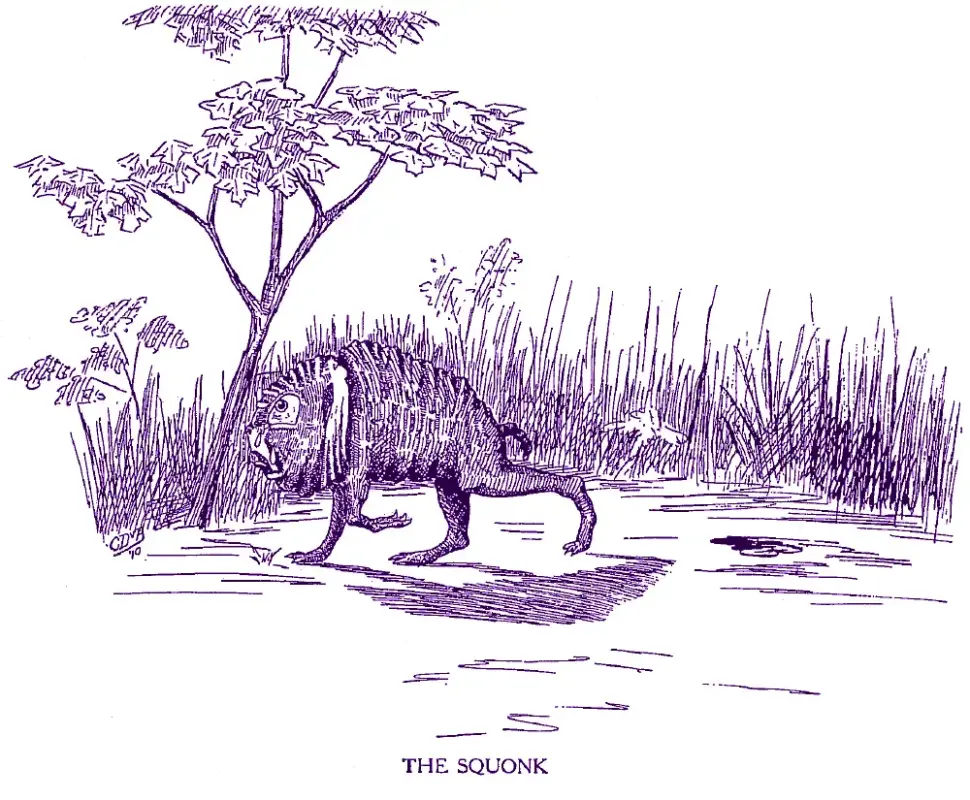

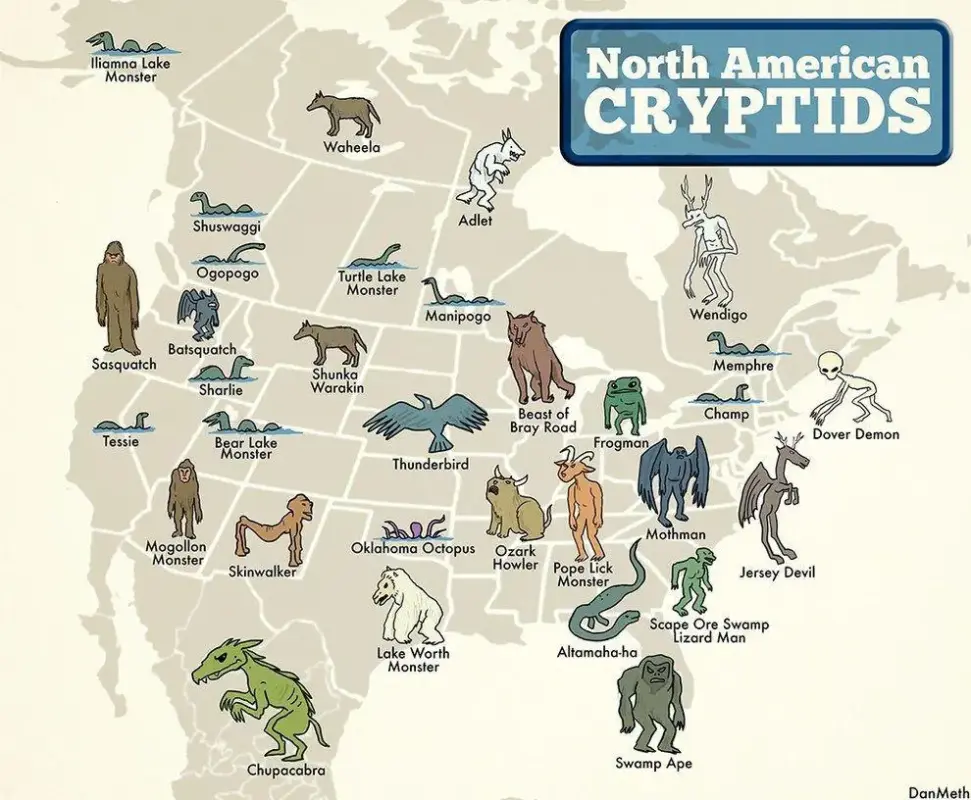

To understand why the Squonk weeps, we must first understand what it is. In the diverse tapestry of North American folklore, specifically the sub-genre known as “Fearsome Critters,” the Squonk holds a unique position. It is not an apex predator. It is a biological anomaly defined by its ugliness and its emotional fragility.

Physical Characteristics

The Squonk is typically described as a forest-dwelling animal, roughly the size of a small pig or a large fox. Its primary feature—and the source of its legendary sorrow—is its skin. The epidermis of the Squonk is described as being several sizes too large for its skeletal frame. This results in deep folds, sagging wrinkles, and a texture often compared to a “misfitting coat.”

Further compounding its unfortunate appearance, the skin is covered in warts, moles, and blemishes. These are not merely cosmetic issues; folklore suggests they are sensitive and prone to irritation, making the creature physically uncomfortable in its own body. This constant physical discomfort, combined with a form of primitive self-awareness regarding its appearance, drives the creature into a state of perpetual depression.

Scientific Classification (Cryptozoology)

Early 20th-century chroniclers gave the Squonk a pseudo-scientific name that perfectly encapsulates its nature: Lacrimacorpus dissolvens.

- Lacrima: Latin for tear.

- Corpus: Latin for body.

- Dissolvens: Latin for dissolving.

Translated, it is the “body that dissolves into tears.” This is not just a poetic description but a literal biological defense mechanism attributed to the species.

The Great Dissolution: A Unique Defense Mechanism

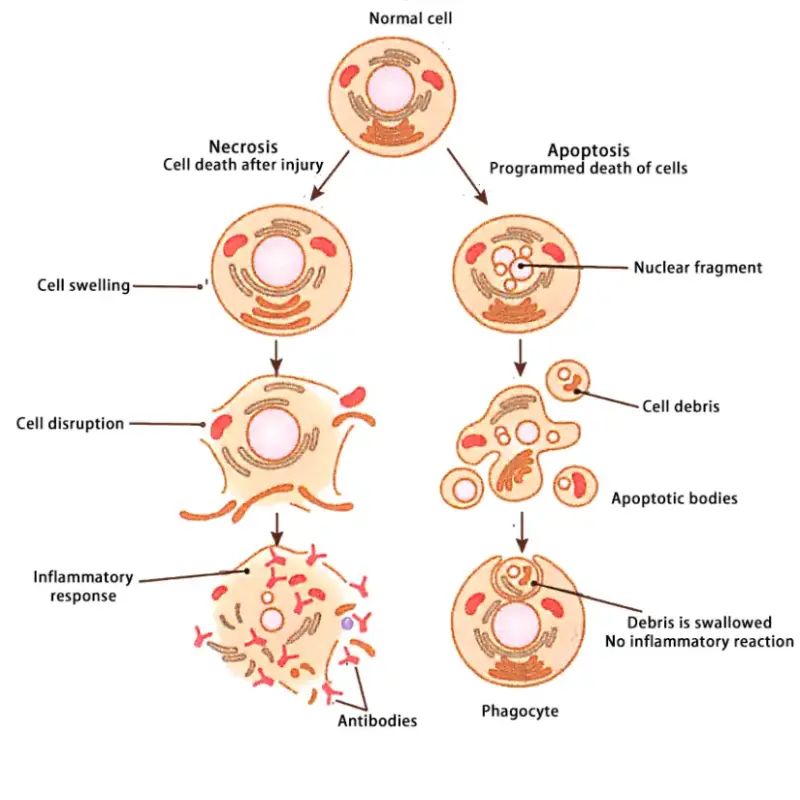

In the animal kingdom, creatures have evolved various methods to evade predation. The porcupine has quills; the skunk has spray; the opossum feigns death. The Squonk possesses perhaps the most radical defense strategy of all: Total Cellular Liquefaction.

When the Squonk feels threatened, cornered, or surprised, its anxiety levels spike. This triggers a rapid chemical reaction within its body. Witnesses and lore keepers describe the creature dissolving into a pool of salty, tear-like fluid. This leaves the predator (or hunter) with nothing but a wet spot on the ground.

Biological Hypotheses

While mainstream biology does not recognize the Squonk, we can look at real-world biological processes to hypothesize how such a mechanism might work if the creature were real.

- Rapid Autolysis: In biology, autolysis is the destruction of cells or tissues by their own enzymes. This usually happens after death. However, a theoretical organism could evolve a “self-destruct” mechanism where stress hormones trigger the simultaneous rupture of lysosomes (cell organelles containing digestive enzymes), turning solid tissue into liquid almost instantly.

- Hyper-Hydrolysis: Some deep-sea creatures, like hagfish, can produce massive amounts of slime and alter their body composition. The Squonk might not be dissolving its bones, but rather rapidly excreting its entire body weight in water and collapsing its loose skin to look like a puddle, allowing it to slip away into the soil.

Origins of the Legend: The Lumberwoods of 1910

The story of the Squonk did not appear in a vacuum. It was formalized and popularized by William T. Cox in his seminal 1910 work, Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods, With a Few Desert and Mountain Beasts.

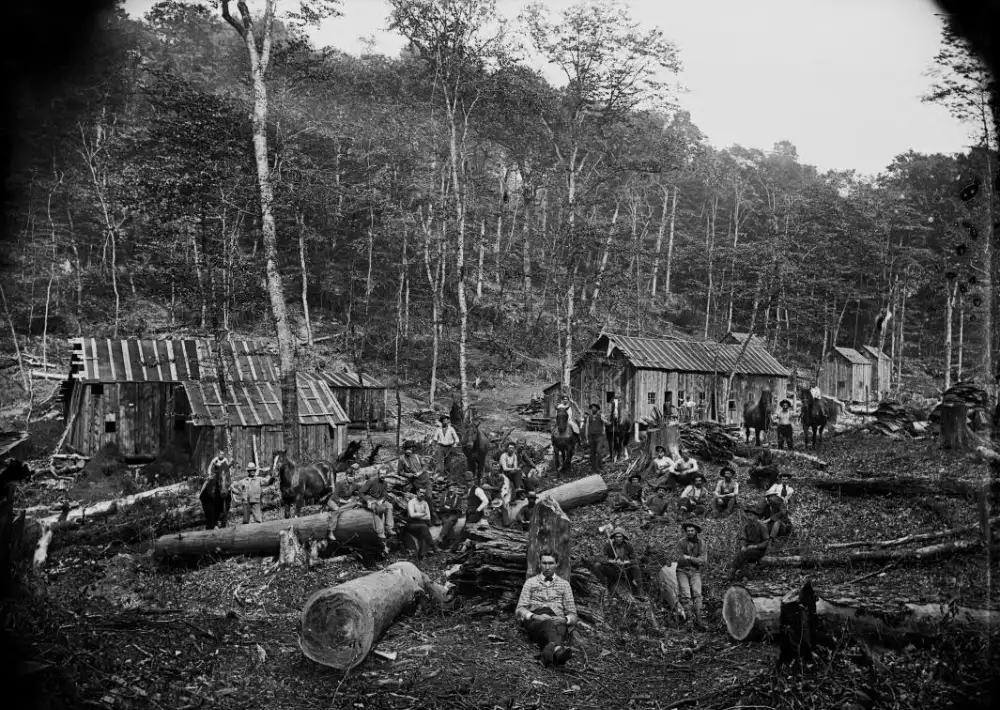

The Golden Age of Logging

To understand the Squonk, you must understand the environment that birthed it. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Pennsylvania was the lumber capital of the world. The massive Hemlock forests were being felled at an industrial rate to provide tannin for leather and wood for a growing nation.

Lumber camps were isolated, all-male communities. The work was dangerous, the hours were long, and the nights were incredibly dark. In this setting, storytelling became a form of currency. The “Fearsome Critters” were born from the tall tales told around the bunkhouse stoves.

These stories served multiple functions:

- Entertainment: A way to pass the long winter nights.

- Hazing: Experienced loggers would send “greenhorns” (new hires) out into the woods to hunt for a Squonk or a Snipe. It was a prank designed to test the gullibility and mettle of the new guys.

- Explanation: The woods are noisy. Branches rub together, wind moans through hollow trees, and animals scream. Attributing the sad, creaking sounds of the forest to the “weeping Squonk” gave a name to the unknown noises of the wilderness.

Habitat Profile: The Hemlock Forests of Pennsylvania

The Squonk is strictly endemic to the Hemlock forests of Northern Pennsylvania. This specific habitat is crucial to the creature’s lore and potential existence.

The Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) creates a unique ecosystem. These trees are evergreen, with dense canopies that block out up to 90% of sunlight. The forest floor beneath a hemlock stand is often free of underbrush, carpeted only in needles, and perpetually cool and damp.

Why Hemlock?

The connection between the Squonk and the Hemlock tree is symbiotic in folklore.

- Camouflage: The bark of an old-growth Hemlock is deeply furrowed, rough, and often covered in moss. The Squonk’s warty, folded skin provides perfect camouflage against the roots of these trees.

- Chemical Environment: Hemlock bark is rich in tannins (tannic acid). The “tears” of the Squonk are often described as acidic or caustic. Living in a high-tannin environment would support the biology of a creature with acidic body chemistry.

- Ecological Grief: By 1910, the Hemlock forests were being decimated. The Squonk can be interpreted as the spirit of the forest itself, weeping for the destruction of its home. As the trees fell, the Squonk had fewer places to hide, mirroring the decline of the wilderness.

Not all cryptids are born from sorrow.

While the Squonk dissolves in its own grief, other legends of the American wilds stand defiant — proud, watchful, and just as unreal. Among them is the Jackalope, a creature of frontier myth where folklore meets fantasy.

Explore the legend that doesn’t weep — it watches

The Hunt: How (Not) to Catch a Squonk

Over the last century, many have tried to replicate J.P. Wentling’s hunt. While we at IHeartCryptids advocate for the observation rather than the capture of cryptids, understanding the historical methods gives us insight into the creature’s behavior.

Tracking the Sadness

You cannot track a Squonk by looking for footprints, as it steps lightly to avoid detection. You track it by sound and moisture.

- The Sound: Hunters listen for a low, gurgling sob. This sound is distinct from the call of a mourning dove or a fox. It is described as a sound of “pure misery.”

- The Trail: The Squonk leaves a wet trail, even on dry days. This is the saline secretion from its constant weeping. Hunters would follow this trail of tears until it ended at a hollow log or a rock crevice.

The Sack Method

Firearms are useless against the Squonk. A bullet would pass through its soft tissue or cause it to dissolve instantly from shock. The traditional method requires:

- A Burlap Sack: Also known as a gunnysack. It must be thick enough to hold a liquid but breathable.

- Mimicry: The hunter must mimic the sound of a distressed animal. The Squonk, being miserable, is sometimes drawn to the misery of others—a “misery loves company” dynamic.

- Speed: Once the creature is located, it must be scooped up immediately.

However, as history shows, this method has a 0% success rate for bringing back a live specimen. The result is always a wet sack and a disappointed hunter.

Scientific Investigations: Real Animals or Pure Myth?

For the skeptics and the scientifically minded, is there a rational explanation for the Squonk? Zoology offers a few candidates that may have inspired the legend.

1. The Eastern Hellbender

The most likely candidate for the Squonk is the Eastern Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis).

- Appearance: The Hellbender is North America’s largest salamander. It grows up to 2 feet long, has loose, frilly skin that looks “too big” for its body, and is generally considered ugly by conventional standards.

- Habitat: It lives in the streams of Pennsylvania.

- Defense: When handled, Hellbenders secrete a copious, thick slime. A lumberjack grabbing one in the dark might feel the creature becoming slippery and “dissolving” out of his grip, leaving only slime (tears) behind.

2. Mange-Ridden Animals

A bear, raccoon, or fox suffering from a severe case of sarcoptic mange loses its fur. Its skin becomes wrinkled, crusted, and warty. These sick animals are often solitary, shivering, and behave erratically. A glimpse of a hairless, shivering, warty creature in the twilight could easily be interpreted as a monster.

3. The “Wet Spot” Phenomenon

The “puddle” left behind by the Squonk has a geological explanation. In the limestone-rich geology of Pennsylvania, small springs can bubble up and disappear quickly. Frost pockets can also melt rapidly in the morning sun. A hunter finding an inexplicable wet spot might invent a story to explain it.

The Squonk in Music and Pop Culture

Despite being a “minor” cryptid compared to Bigfoot, the Squonk has achieved a cult status in pop culture, particularly in the music industry. Its story of sadness resonates with artists.

Steely Dan and the Tears

In the 1974 song “Any Major Dude Will Tell You” by Steely Dan, the lyrics ask: “Have you ever seen a squonk’s tears? Well, look at mine.”

Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, the masterminds behind Steely Dan, used the Squonk as a high-brow reference to pathetic male vulnerability. It cemented the Squonk as the patron saint of the sad and the misunderstood.

Genesis: A Trick of the Tail

The British progressive rock band Genesis dedicated an entire track to the creature on their 1976 album A Trick of the Tail. The song, titled simply “Squonk,” retells the William T. Cox story in detail.

- Lyrics: “All in all you are a very dying race / Placing trust in a cruel world.”

The song explores the irony of the hunter who captures the Squonk only to be left with nothing. It frames the Squonk’s dissolution not just as a defense, but as a final act of autonomy—it chooses to vanish rather than be owned.

Squonk (2007 Remaster)

Cultural Significance: Why We Love the Loser

Why does the Squonk persist in 2025? Why do we have Squonkapalooza, a festival in Pennsylvania dedicated to this weeping beast?

The answer lies in human psychology. We live in an era of curated perfection, where social media demands we show only our best selves. The Squonk is the antithesis of this. It is ugly, it is sad, and it wants to hide.

- Empathy: We see ourselves in the Squonk. Everyone has felt uncomfortable in their own skin.

- Regional Pride: For Pennsylvanians, the Squonk is their monster. It represents the gritty, rough-around-the-edges character of the Rust Belt and the deep woods.

- Survival: Despite its fragility, the Squonk survives. It hasn’t been caught. Its sadness keeps it safe. There is a strange resilience in that.

Comparative Cryptozoology: The Squonk’s Cousins

The Squonk is part of a larger family of entities. To understand its place in the ecosystem, we must compare it to other regional legends.

The Hidebehind

Also a creature of the lumberwoods, the Hidebehind is defined by its elusiveness. While the Squonk hides due to shame, the Hidebehind hides to hunt. They are the yin and yang of forest invisibility.

The Hodag

Hailing from Wisconsin, the Hodag is ugly like the Squonk but reacts with aggression and ferocity. The Squonk represents the “flight” response, while the Hodag represents the “fight” response to the encroachment of civilization.

The Jersey Devil

A neighbor to the south in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. The Jersey Devil is loud, screeching, and mobile. The Squonk is quiet, sobbing, and sedentary.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

At IHeartCryptids, we receive inquiries daily about this creature. Here are the most common questions answered.

Q: Is the Squonk dangerous to humans?

A: Absolutely not. The Squonk is arguably the safest cryptid to encounter. It has no desire to attack; it only wants to escape.

Q: Can I keep a Squonk as a pet?

A: No. Even if you could catch one without it dissolving, the ethical implications are severe. The creature is defined by its misery. Keeping it in a tank would be cruel, and it would likely dissolve from the stress of captivity within hours.

Q: What does a Squonk eat?

A: Folklore is silent on this, but based on its physiology and habitat, we hypothesize it is an omnivore or detritivore, feeding on fungi, hemlock roots, and forest insects.

Q: Is the Squonk extinct?

A: We cannot say for sure. However, the decline of the Hemlock forests due to the woolly adelgid pest places the Squonk’s theoretical habitat at risk. If the trees die, the shadows disappear, and the Squonk has nowhere left to weep.

A Guide to “Squonk Spotting” in 2025

If you are brave enough to venture into the PA Wilds to look for the Squonk, you must do so with respect.

- Go at Twilight: This is the crepuscular hour when Squonks are most active.

- Visit Old Growth: Look for state parks like Cook Forest State Park or the Allegheny National Forest where ancient Hemlocks still stand.

- Listen, Don’t Look: Your ears are your best tool. Listen for the sobbing sound that doesn’t match any known bird or mammal.

- Leave No Trace: If you find a wet spot that sizzles, take a photo, but do not disturb it. That puddle was once a living thing.

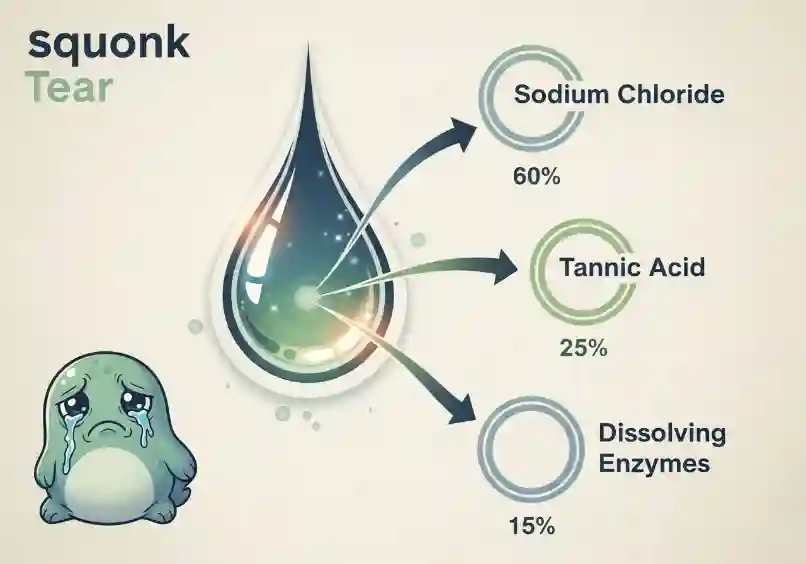

Deep Dive: The Chemistry of Tears (Speculative Science)

Let us return to the “wet spot” left behind. If we analyze this through a chemical lens, what is in a Squonk’s tears?

Normal animal tears contain water, electrolytes, and proteins (lysozyme). Squonk tears would likely be hyper-saline and highly acidic. The “sizzle” described in lore suggests an exothermic reaction.

- PH Level: Likely around 3.0 or 4.0 (similar to acid rain or vinegar).

- Composition: High concentrations of urea or ammonia, which would aid in the rapid breakdown of organic tissue during the dissolution phase.

This chemical profile suggests that the Squonk is a walking biological battery, storing potential chemical energy to be released in a defensive burst.

The Legacy of the Squonk

The Squonk is a reminder that not all monsters are monsters. Some are just sad animals trying to survive in a world that is shrinking.

In the early 1900s, the Squonk was a joke—a way for lumberjacks to laugh at the darkness. Today, it is a symbol of environmental fragility and emotional honesty. We tell the story of the Squonk not to mock it, but to protect it. It reminds us that there are still mysteries in the deep woods, and some of them just want to be left alone.

Join the Hunt (Responsibly)

Are you fascinated by the strange and the unexplained? The Squonk is just the beginning.

- If you want to support the preservation of cryptid lore, check out our Cryptid Decor collection.

- Want to cuddle cryptids without it dissolving? We have the solution. Visit our cryptid merchandise.

- Continue your education with our Cryptid Files, where we explore everything from Bigfoot to the Mothman.

- For the ultimate overview, read our A Cryptozoologist’s Field Guide: The A-Z of 50+ Legendary Cryptids.

Final Thoughts: The Tears That Bind Us

As you scroll through your phone in the safety of your home, remember J.P. Wentling standing in the cold, holding an empty, wet sack. He went looking for a monster and found a tragedy.

The legend of the Squonk asks us a simple question: Do we have enough empathy for the ugly things? At IHeartCryptids, we believe the answer should be yes. Because in the end, we are all a little bit like the Squonk—just trying to make it through the night without dissolving.

Data & Statistics: The Squonk at a Glance

| Attribute | Detail |

| Common Name | The Squonk |

| Latin Name | Lacrimacorpus dissolvens |

| First Recorded | 1910 (William T. Cox) |

| Status | Folklore / Cryptid |

| Defense | Dissolution into liquid |

| Sound | Weeping / Sobbing |

| Primary Range | Hemlock Forests, PA |

| Danger Level | Zero |

Disclaimer: This article explores folklore and cryptozoology. No Squonks were harmed or dissolved in the making of this content. Please respect wildlife and local regulations when exploring Pennsylvania state parks.