Cryptid Files

Cadborosaurus: History, Evidence, and Sightings of BC’s Serpent

August 1968. Pirate’s Cove, De Courcy Island.

Captain William Hagelund was not looking for monsters that evening. He was looking for a quiet anchorage. The sun had dipped below the tree line of the Gulf Islands, casting long, bruised shadows across the water. His family slept below deck, lulled by the gentle lap of the Salish Sea against the hull.

Then he saw it.

Something was breaking the surface near his stern. It wasn’t a seal. It wasn’t a log. It was swimming with a vertical undulation that defied the mechanics of local fish. Hagelund, a man of practical experience and maritime grit, dropped a net. He didn’t expect to catch anything, yet minutes later, he was hauling a writhing, terrified creature onto the deck. It was sixteen inches long, with a primitive, camel-like head, tiny front flippers, and a spade-shaped tail. It hissed. It blinked.

For hours, Hagelund guarded a creature that science said did not exist. He had the physical proof of the Cadborosaurus in a bucket of seawater. But as the creature weakened, thrashing in distress, compassion overrode curiosity. He tipped the bucket. The creature slipped back into the dark water, taking the undeniable proof of a century-old mystery with it.

This is not just a campfire story. It is one of the hundreds of logged encounters in the archives of IHeartCryptids.com. We do not deal in rumors; we deal in the unexplained history of our natural world. Today, we open the file on the beast of British Columbia.

1. Defining the Deep Sea Enigma: What is Cadborosaurus?

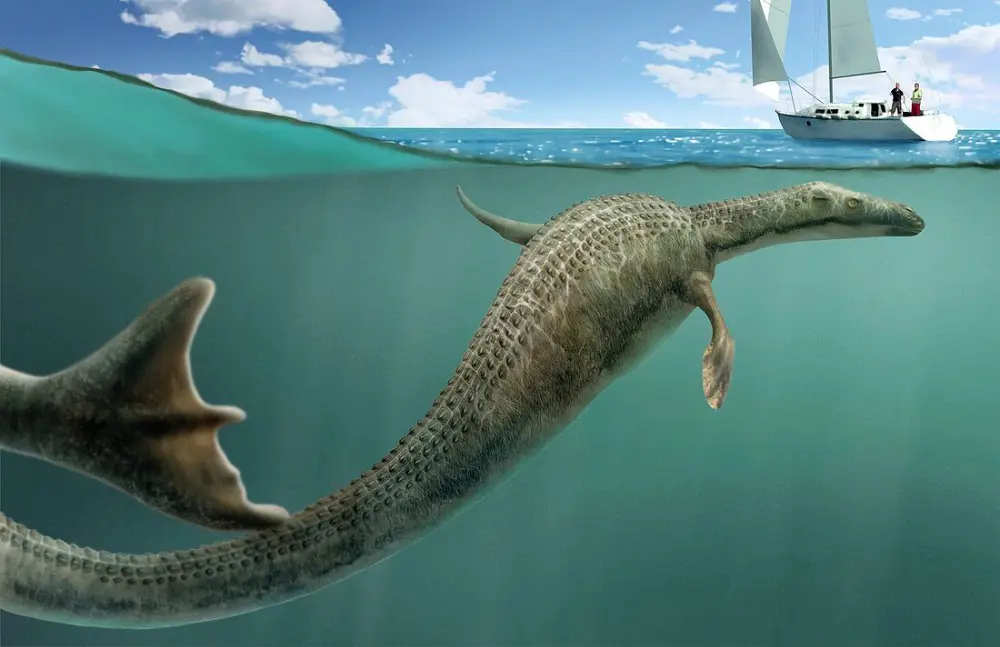

To understand the creature, we must first strip away the tabloid sensationalism and look at the consistent biological data reported over the last century. Cadborosaurus willsi, affectionately known as “Caddy,” is not a dragon of fantasy. The descriptions are remarkably consistent, suggesting a biological organism rather than a mythical chimera.

Witnesses, ranging from seasoned fishermen to marine biologists, describe a serpentine animal inhabiting the deep, cold waters of the Pacific Coast of North America. The primary range extends from Vancouver Island in British Columbia down to San Francisco Bay.

Morphological Characteristics

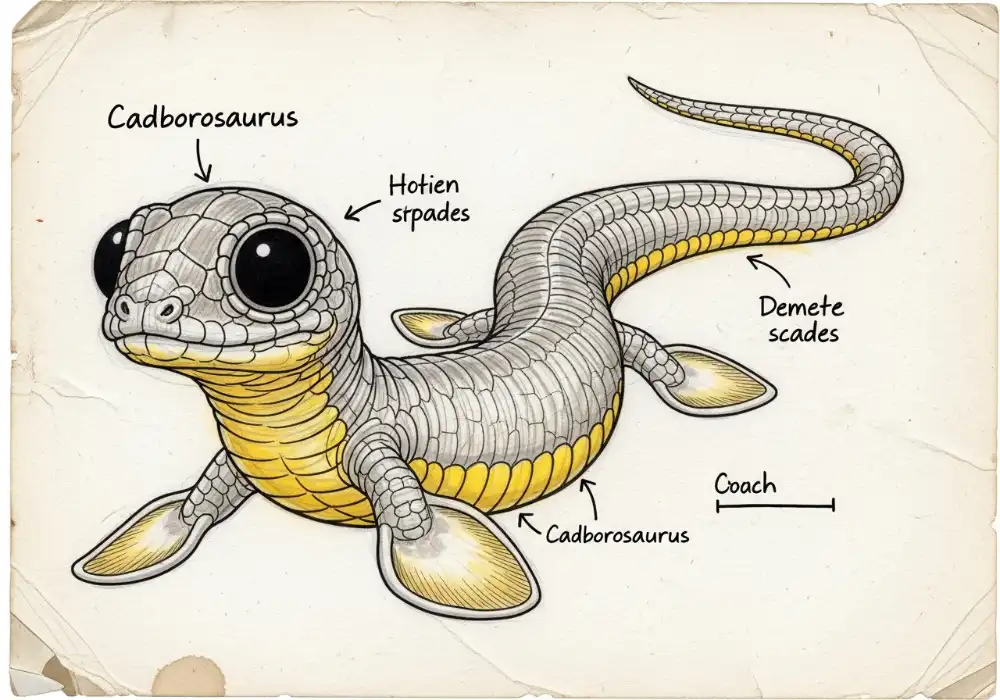

Based on data compiled from over 300 sightings, the creature possesses specific attributes that separate it from known animals like the Oarfish or Basking Shark.

- Head: Often described as camel-like or horse-like, with large eyes and distinct nostrils.

- Neck: Slender and elongated, capable of rising several feet out of the water.

- Body: Tubular and serpentine, ranging from 15 to 50 feet in length.

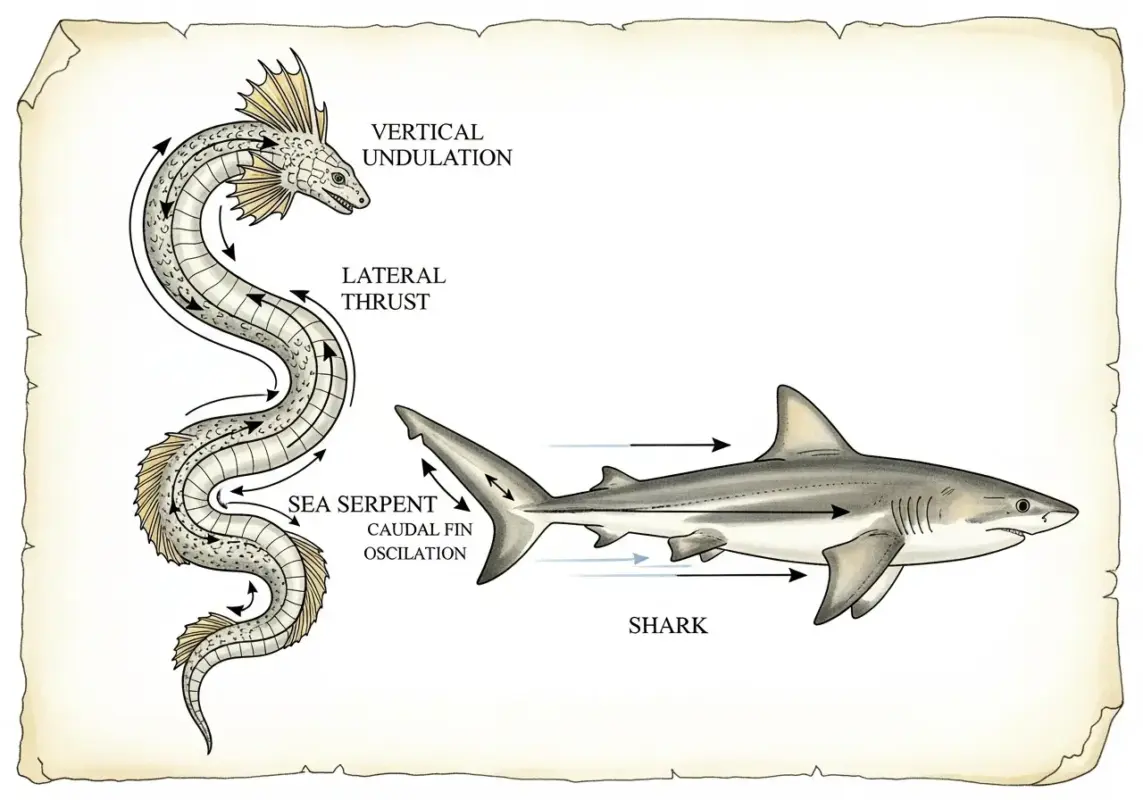

- Locomotion: Vertical undulation (moving up and down like a caterpillar), which is a key distinction from the side-to-side motion of sharks and reptiles.

- Appendages: Many reports mention a pair of front flippers and a split or spade-shaped tail.

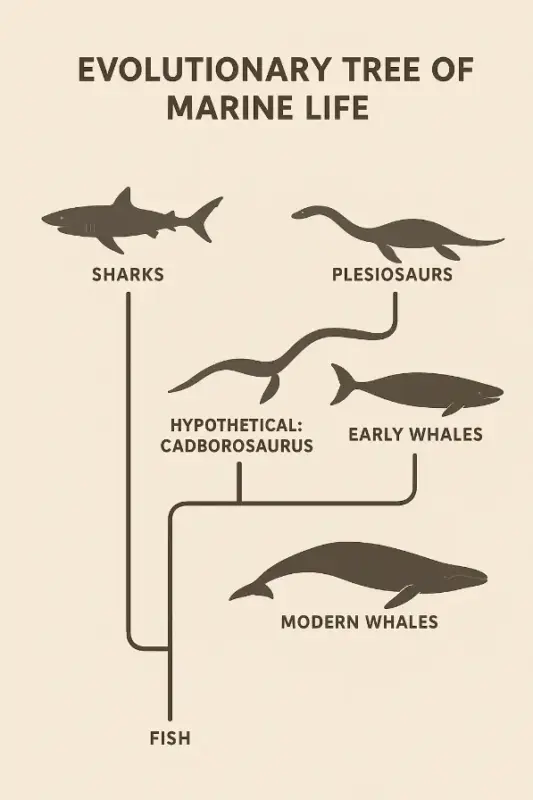

The classification of this creature remains a subject of intense debate. In 1995, Dr. Paul LeBlond, a professor of oceanography at the University of British Columbia, and Dr. Edward Bousfield, a chaotic zoologist, formally proposed the name Cadborosaurus willsi. They argued that the creature displayed characteristics of a reptile, yet its motion and tolerance for cold water suggested a mammal. This contradiction is what makes the investigation so compelling.

We are looking for an animal that fits into the gaps of the fossil record, perhaps a convergent evolution where a reptile adapted to cold water, or a prehistoric whale that retained a serpentine form.

2. Ancient Origins: The Indigenous Record

Long before Archie Wills, the editor of the Victoria Daily Times, coined the name “Cadborosaurus” in 1933, the creature was well known to the First Nations people of the Pacific Northwest. This is not a modern invention; it is a part of the region’s cultural and natural history.

The Chinook people referred to a similar creature as the Hias-chuck-tuck (Big Water Snake). The Manhousat people of Sydney Inlet tell of the Mih-ih-nah-a, a massive beast with a head like a horse that could sink canoes. These were not spiritual entities in the sense of ghosts; they were treated as physical dangers of the ocean, animals that required respect and avoidance.

One of the most compelling pieces of historical evidence is the prevalence of “sea wolf” or serpentine imagery in coastal art dating back thousands of years. Anthropologists suggest that while some imagery is stylized, the consistency of the “horse-head” motif across different tribes—who spoke different languages—points to a shared physical observation.

When we analyze these oral histories through the lens of modern cryptozoology, we see a pattern. The sightings often occur in inlets and bays, suggesting the creature comes close to shore, perhaps to feed on herring runs or sea lions. This behavior mirrors the modern sightings in Cadboro Bay, linking the past to the present.

3. The 1937 Naden Harbour Carcass: The Smoking Gun?

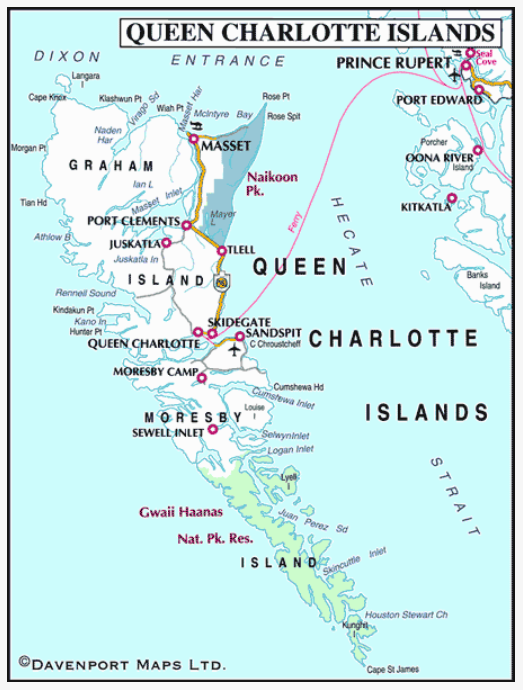

If you are looking for Informational (Evidence), this is the pivotal moment in Caddy lore. In October 1937, whalers at the Naden Harbour whaling station on Haida Gwaii (formerly Queen Charlotte Islands) made a gruesome discovery.

Inside the stomach of a massive sperm whale, they found the semi-digested remains of a creature they could not identify.

The station manager, reluctant to simply discard the oddity, laid it out on a table. It measured roughly 10 feet long (though some parts were missing due to digestion). It had a camel-like head, a long neck, a serpentine body, and a tail that looked nothing like a fish.

The Evidence Captured

G.V. Boorman, one of the workers, snapped several photographs. These images remain the most controversial and significant evidence in the search for Cadborosaurus. They show a carcass that does not easily fit into the taxonomy of known marine life.

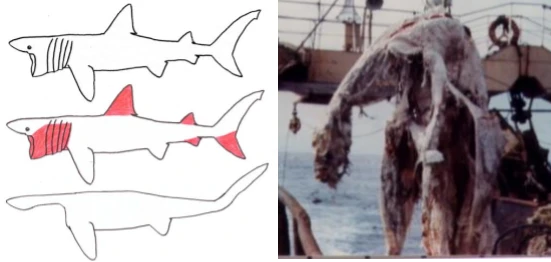

Skeptics have long argued that the Naden Harbour carcass was merely a fetal baleen whale. They suggest the decomposition process distorted the features, making the snout look like a camel’s nose. However, Dr. Bousfield and Dr. LeBlond countered this argument effectively in their research.

The Counter-Argument:

- The Spine: A fetal whale has a rigid spine designed for a massive body. The Naden carcass showed a spine that was clearly flexible and serpentine.

- The Tail: Baleen whales have horizontal flukes. The photos of the carcass show a tail structure that appears to be decaying in a way that implies a different skeletal makeup.

- The Skin: Witnesses described the skin as having short, fur-like hair or a very smooth texture, inconsistent with a fetal whale at that stage of development.

The tragedy of the Naden Harbour incident is that the specimen was lost. Some say it was shipped to a museum in Victoria and misplaced; others say it was simply discarded after the photos were taken. We are left only with the images and the testimony, a haunting “what if” that drives researchers to this day.

Map of Haida Gwaii Naden Harbour

4. The Golden Age of Sightings: 1933-1937

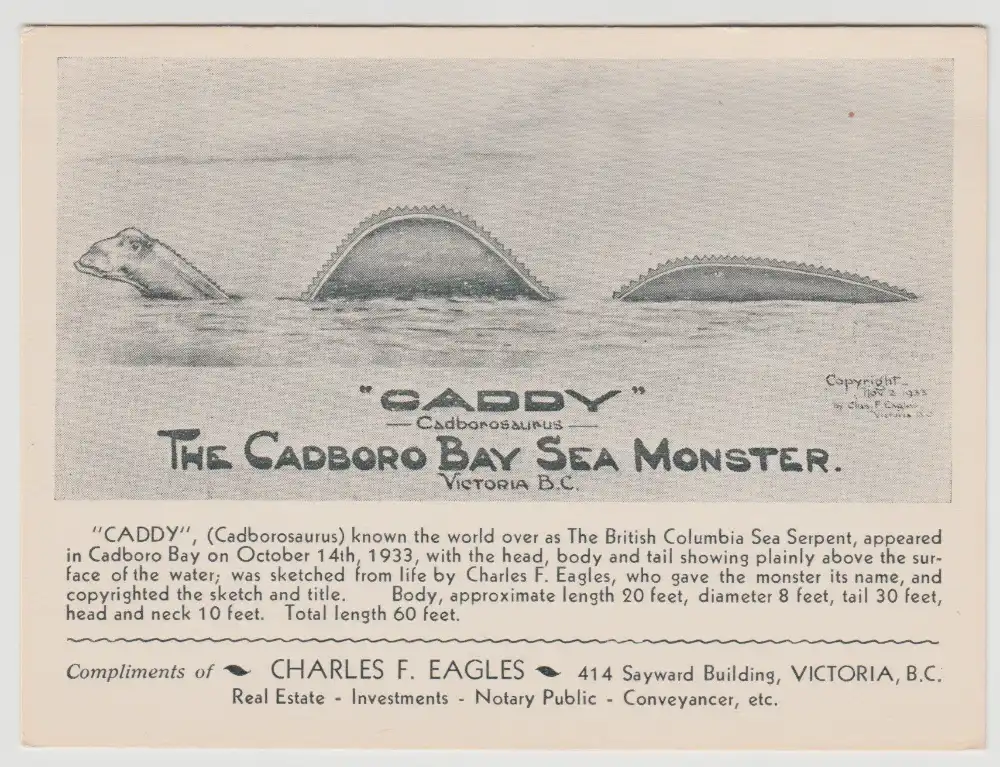

While the Naden Harbour carcass is the physical anchor, the early 1930s were the “Phenomenal Week” equivalent for Cadborosaurus. In October 1933, Major W.H. Langley, a highly respected barrister and Clerk of the BC Legislature, reported seeing the creature.

Langley was sailing his yacht near Chatham Island when he saw a “huge dome” break the water, followed by a serpentine back. He estimated the creature was at least 80 feet long. When a man of Langley’s social standing puts his reputation on the line, the public listens.

Following Langley’s report, the floodgates opened. Two duck hunters in 1934 described a beast that rose out of the weeds to swallow a wounded duck whole. A group of fishermen near the Gulf Islands reported a creature keeping pace with their boat at 30 knots—a speed that rules out many sluggish deep-sea fish.

This era cemented the creature’s name. Archie Wills, the news editor, realized the public needed a handle for the monster frequenting Cadboro Bay. He ran a contest, and “Cadborosaurus” was the winner. While the name sounds whimsical, the reports filed during this time were anything but. They were detailed, consistent, and came from credible witnesses who had nothing to gain by being ridiculed.

While Cadborosaurus dominates the folklore of Canada’s Pacific coast, the world’s most famous lake-dwelling mystery still belongs to the Loch Ness Monster. If you’re fascinated by cryptids of the deep, explore our Loch Ness collection below.

5. The Hagelund Capture: A Hands-On Examination

We must return to the story of Captain William Hagelund. His 1968 encounter is unique because it moves beyond observation into interaction.

Hagelund was an experienced whaler and mariner. He knew what marine life in the Pacific Northwest looked like. He knew what a pipefish was. He knew what an eel was. What he caught that night in Pirate’s Cove was neither.

Key Biological Observations by Hagelund:

- Ventral Scales: He noted hard, plate-like scales on the underbelly, yellow in color. This suggests a creature adapted for moving against rocks or the sea floor, a trait seen in some reptiles.

- The Tail: He sketched a tail that was spade-like, not the tapered tail of an eel.

- Respiration: The creature breathed air. It did not have gills flapping; it had nostrils. This eliminates 90% of fish candidates.

Hagelund did not speak of this encounter for years, fearing ridicule. It wasn’t until LeBlond and Bousfield began their serious academic inquiry that he came forward with his logbook. His hesitation adds to his credibility; he sought no fame, only answers.

6. Scientific Theories: Fact-Checking the Myth

To maintain our standard of Informational (Fact-Checking), we must analyze the skeptics’ arguments. Science demands rigorous testing of hypotheses. If Caddy is real, what is it?

The Basking Shark Hypothesis

The most common explanation for “sea serpent” carcasses is the decomposing Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus). When these massive sharks rot, their heavy jaws and gills fall off first, leaving a small, cranial stump that looks like a “camel head” attached to a long spine (the backbone). This is known as a “pseudoplesiosaur.”

Critique: While this explains washed-up carcasses, it does not explain living sightings. A rotting shark does not swim at 30 knots with its head held high out of the water. It also does not explain the fur or hair reported by some witnesses.

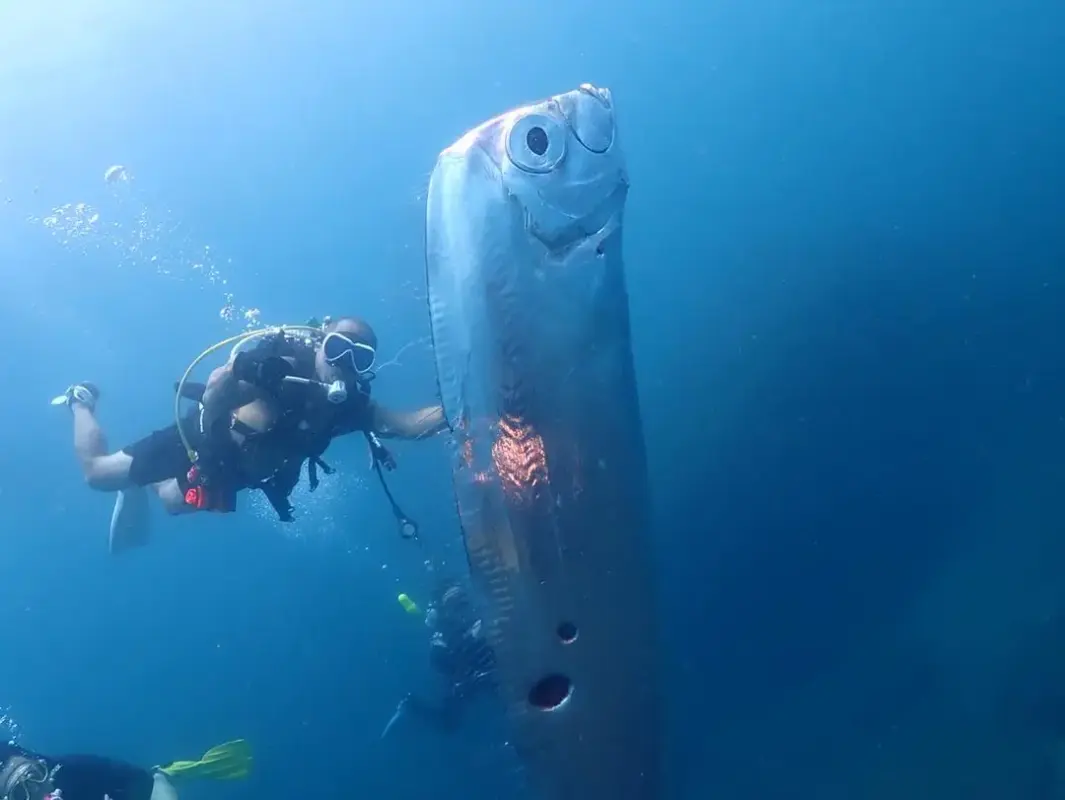

The Oarfish Hypothesis

The Giant Oarfish (Regalecus glesne) is a long, serpentine fish that can reach lengths of 30 feet. They have a red crest that could look like a mane.

Critique: Oarfish are deep-sea dwellers that usually only surface when dying. They swim vertically or hold themselves straight; they do not undulate vertically like a caterpillar. Furthermore, they lack the distinct head shape and the intelligence often attributed to Caddy.

The Pipefish Hypothesis

Some suggest Hagelund caught a Bay Pipefish.

Critique: Pipefish are rigid, possess small mouths, and do not have the muscular articulation Hagelund described. A pipefish is like a pencil; the creature Hagelund held was muscular and flexible.

The LeBlond-Bousfield Hypothesis

The most exciting scientific theory is that Cadborosaurus willsi is a surviving lineage of plesiosaurs or, more likely, a phylogenetically distinct class of vertebrates that bridges the gap between Reptilia and Mammalia. They propose it is warm-blooded, which accounts for its high energy and tolerance for the frigid North Pacific waters.

7. Analyzing the Habitat: The Salish Sea

Why here? Why does this creature frequent the complex waterways between Vancouver Island and the mainland?

The geography of the Salish Sea is unique. It is a labyrinth of deep fjords, strong currents, and nutrient-rich waters. The depths here can plunge to over 2,000 feet, providing ample hiding spots for a large predator.

Key Locations for Caddy Watchers:

- Cadboro Bay: The namesake location. Shallow, calm, and rich in marine life.

- Chatham Islands: The site of Major Langley’s sighting.

- San Francisco Bay: Surprisingly, there have been twin reports of Caddy-like creatures here, suggesting a migration route.

- Gulf Islands: The many coves (like Pirate’s Cove) offer shelter for breeding or resting.

From an oceanographic perspective, this region is a “marine highway.” The abundance of salmon and herring runs provides the caloric density required to support a large predator. If Caddy exists, it is likely following the food.

8. Modern Sightings: The 21st Century

Is Caddy still out there? As of November 2025, reports continue to trickle in.

In 2009, a resident of Kelly Bay filmed a disturbance in the water showing humps moving against the current. In 2016, a ferry passenger near Nanaimo reported a “long neck” surfacing near the wake of the ship.

The proliferation of smartphones has, paradoxically, not led to a clear photo. This is the “blobsquatch” problem. However, modern technology offers new avenues for detection. Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling involves testing water samples for genetic material shed by animals.

A Proposed Solution:

IHeartCryptids advocates for a targeted eDNA study in Cadboro Bay during the salmon runs. If there is an unknown large vertebrate swimming there, its DNA is in the water. We don’t need a body; we need a sequence.

9. Cultural Impact: Caddy in the Community

Victoria, BC, has embraced its monster. Unlike the terrifying depictions of other cryptids, Caddy is often seen as a benevolent, if elusive, neighbor.

Walk through Cadboro-Gyro Park, and you will see the famous concrete sculpture of Caddy. Children climb on its coils. It is a testament to how deeply this legend is woven into the local identity. There are books, documentaries, and even local festivals that celebrate the mystery.

However, this commercialization can be a double-edged sword. It trivializes the biological reality for researchers. It is hard to get funding for a “monster hunt” when the monster is a playground mascot. Yet, the existence of the statue proves one thing: the eyewitness accounts were so numerous and so impactful that the city could not ignore them.

10. A Guide for the Aspiring Cryptozoologist

So, you want to find Caddy? This is Navigational (Locational) advice for the serious investigator.

You cannot simply stare at the ocean. You need a strategy.

Step 1: Timing is Everything.

Most sightings occur during the summer months or during herring spawning seasons. The water is calmer, and the food is abundant. Dawn and dusk are the prime hunting hours.

Step 2: The Gear.

Binoculars are good; drone technology is better. A drone can scan a bay in minutes and offers a top-down view that eliminates the distortion of light on waves.

Step 3: What to Look For.

Don’t look for a monster. Look for the wake. A boat wake spreads out in a V. A swimming animal creates a different disturbance pattern. Look for birds diving; they often follow predators that drive baitfish to the surface.

11. Is Cadborosaurus Dangerous?

There are almost no reports of aggression toward humans. The “Manhousat” legends speak of danger, but modern accounts describe a creature that is shy and skittish.

In the 1930s, there were fears that Caddy might capsize small boats, but this seems to be more about the animal’s size than its intent. Like any wild animal, a 40-foot creature could accidentally harm a human, but Caddy does not appear to be a man-eater.

12. The Verdict: Hoax or Reality?

We circle back to the core question: Is Cadborosaurus real?

The evidence is a tapestry of circumstantial proof. We have the Naden Harbour photos (compelling but inconclusive). We have the Hagelund capture (credible testimony but no physical specimen). We have thousands of eyewitness accounts from credible observers.

It is statistically unlikely that all these people are lying or mistaken. The specific details—the camel head, the vertical undulation, the mane—appear too consistently to be mass hallucination.

From a scientific standpoint, the ocean is vast and largely unexplored. The discovery of the Coelacanth proved that “extinct” creatures can hide in the depths. The Megamouth Shark was not discovered until 1976. Is it so impossible that a population of large, serpentine animals exists in the nutrient-rich fjords of BC?

We believe the file on Cadborosaurus is far from closed. It is an active investigation.

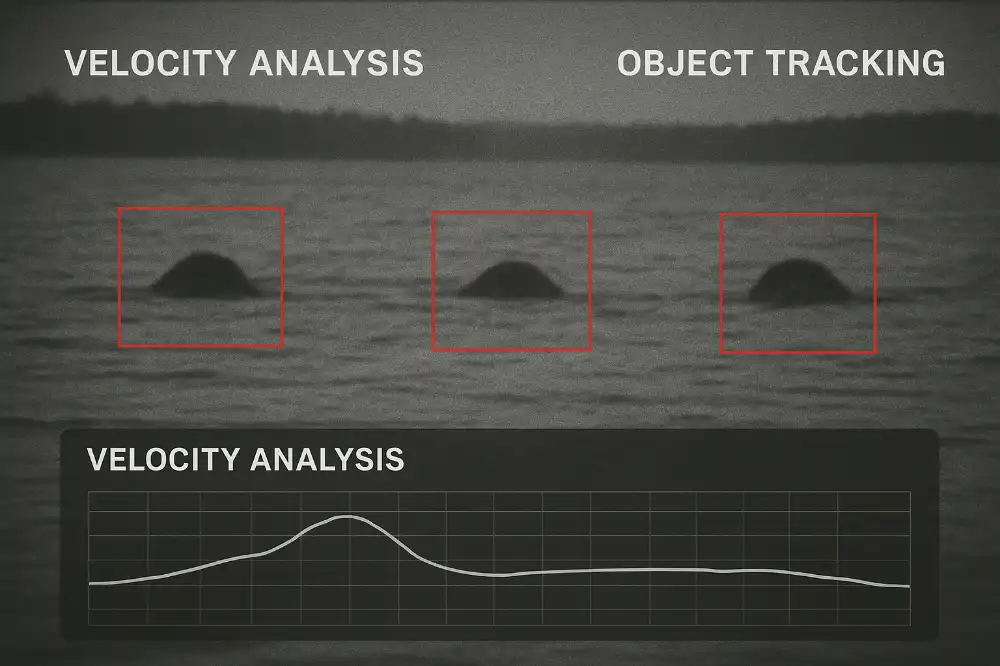

13. Video Evidence & Analysis

While high-definition video remains elusive, several clips have surfaced over the years that warrant analysis.

2009 Cadborosaurus Video (filmed by Kelly Nash) – Enhanced and Stabilized

This video shows a distinct series of humps moving against the current. While skeptics claim it is a wave train or a log, the movement suggests independent propulsion.

14. Conclusion: The Watch Continues

The story of Cadborosaurus is the story of the Pacific Northwest itself—wild, deep, and holding its secrets close. Whether Caddy is a relic of the dinosaur age, a misidentified shark, or a new species waiting for classification, it represents the magic that still exists in our world.

At IHeartCryptids, we stand on the shore and watch. We archive the history so that when the next carcass washes up, or the next captain catches a “baby” in their net, we will be ready to ask the right questions.

Until then, keep your eyes on the water. You never know what might break the surface.

Explore the Mystery Further with IHeartCryptids

If the legend of Cadborosaurus has captured your imagination, dive deeper into the world of cryptozoology with our exclusive collections and files. Support the search for the truth.

- Wear the Legend: Shop Cryptid Apparel & Decor

- Discover More Beasts: Browse All Cryptid Products

- Read the Archives: Access the Cryptid Files

- The Ultimate Guide: A Cryptozoologist’s Field Guide: The A-Z of 50+ Legendary Cryptids